Letter thirteen

January 5, 2025

Dear Reader,

Wind moves through the grove of trees surrounding me. Lateral snowdrifts fall, creating a hushed rustle—a soft fizz—as they settle on the English ivy-covered understory. The forest hums with a quiet only winter knows.

As the season settles in, I find myself leaning into that quiet. In my studio, I felt an urge to clear everything out—decluttering bookshelves, carrying evergreen boughs to the compost pile. I craved blank space—empty-to-be-filled—and the clarity it offers.

In the betwixt days before the new year, I deleted social media apps from my phone, the ones that siphon away the now. I spent hours reading idly, the window cracked open, closely observing my paperwhites, Narcissus papyraceus,—watching their strap-like leaves tilt subtly to follow the sun’s arc.

Then, on a warmer-than-usual New Year’s Day, the first cluster of blooms separated from its spathe. By afternoon, the flowers began to open—six-pointed stars unfolding with a faint musky smell, somewhere between petrichor and jasmine.

I followed suit, gravitating toward the warmth and dedicating myself to decluttering and organizing the working garden spaces—the real work of winter gardening.

In the process, I found a forgotten bag of Narcissus bulbs—Obdam, White Cheerfulness—and though we’re in the midst of winter, I decided to take my chances and pot them up, creating a Monty-esque ‘table flowers’ garden visible just outside the window of my writing desk.

During winter, the stillness is no longer something to be filled or fixed—it is simply there, unfolding.

Lately, I’ve been noticing patterns of thoughts and cyclical feelings that seem to emerge only in the winter months. The absence of external noise allows an inner stillness to rise up, revealing parts of myself I don’t often see. In this solitude, the boundaries between myself and the world soften.

This softening creates space for true connection—both with myself and with others. But there’s also a familiar melancholic feeling that winter carries, one I had left behind in the busyness of spring and the exuberance of summer. It was the familiar ache of loneliness.

Loneliness is a feeling that’s difficult to explain and even harder to confess. When I’m in the garden or submerged in the natural world, I’m usually alone, yet I rarely encounter loneliness. Instead, I find a deep sense of belonging.

It’s when I’m surrounded by people that the subtle ache of loneliness seems to surface.

Virginia Woolf, in her 1929 Diary, seemed to find this sense of inner loneliness worth examining, writing: “If I could catch the feeling, I would: the feeling of the singing of the real world, as one is driven by loneliness and silence from the habitable world.”

At a Christmas party weeks ago, I felt the poignancy of this inner loneliness. I was selling wreaths of cedar and dried flowers I had collected throughout the growing season. I was in the company of others, yet I didn’t really know anyone there. Surrounded by flowers, I had the melodramatic thought, all my friends are flowers.

What is it like to feel lonely? It’s a dull ache, a lump in your throat. It’s the feeling of being seen but not known—not really known.

When I usually encounter loneliness, I tend to reject it outright. It comes and goes—not just in winter—but winter creates an environment where it feels sharper, more unavoidable.

This time, instead of turning away from it, I decided to lean in. I wanted to understand my loneliness—to explore how those deeply connected to the natural world interact with this feeling, how there’s more to it than what’s immediately felt.

Leaning into loneliness felt counterintuitive at first. I wanted to turn away, to busy myself, to fill the empty space with noise or movement. But instead, I stayed. I let it settle around me like a dense fog.

During that time, I began jotting down notes in my morning pages—fragments of thoughts, studies, and words from others who had pulled at the strings of this thread before me.

Despite how isolating it feels, loneliness is not a rare or unique affliction. Recent studies suggest that approximately 50% of American adults report experiencing measurable levels of loneliness. Nearly 1 in 3 adults frequently feel lonely. These numbers surprised me—not because I didn’t believe them, but because we so often feel like we’re alone in our aloneness when in fact, loneliness is something deeply human, shared across time and place.

Loneliness doesn’t always arise from physical isolation. Epictetus wrote over a thousand years ago, “For because a man is alone, he is not for that reason also solitary; just as though a man is among numbers, he is not therefore not solitary.” How true that feels. I’ve known loneliness most vividly not in empty rooms, but in crowded ones like the Christmas party—in places where everyone seemed to know someone, where laughter carried across a room I felt separate from. And yet, when I’m in the garden or walking beneath branches, truly alone, I rarely feel lonely. Instead, there’s a sense of being deeply accompanied—by the wind, by the trees, by something larger and older than myself.

Virginia Woolf seemed to understand this paradox well. She wrote, “How much better is silence; the coffee cup, the table. How much better to sit by oneself like the solitary sea-bird that opens its wings on the stake.” Her words remind me that loneliness, when not resisted, can become something else entirely—a still, generative space. It can become fertile ground for thought, for clarity, for noticing the smallest and most miraculous details of the world. There’s richness in it, if I allow myself to stay long enough to see it.

Mary Oliver captures this same stillness in her poem How I Go to the Woods. She doesn’t retreat to the woods to escape loneliness but to meet it—to sit with it beneath the trees and feel its edges soften.

And in Wild Geese, she writes,

“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting—

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

There’s such solace in those lines. Loneliness, Oliver seems to say, isn’t a void—it’s an opening.

The world itself is constantly reaching out to meet us over and over, calling us back into connection, reminding us that we belong. I think about those words often when I’m outside, watching the frost dissolve in the sun or hearing the faint call of a bird somewhere far off. Nature has a way of transforming loneliness into something closer to belonging, a reminder that we are part of something vast and ongoing.

Perhaps, most importantly, I began to understand that loneliness isn’t a failure. Olivia Laing, in her memoir, The Lonely City writes, “Loneliness, longing, does not mean one has failed, but simply that one is alive.” It’s easy to convince ourselves that loneliness is a sign of something broken, something to fix or hide. But Laing reframes it as evidence of our aliveness—proof of our capacity for connection and our need for it.

Winter has a way of laying truths bare. Loneliness can feel stark and unyielding like the landscape in these months. But it also holds something incredibly tender—something necessary. If I can stay with it—if I can resist the urge to fill or silence it—it seems to shift. It becomes a space, empty-to-be-filled, an offering.

This has been the free version of my newsletter, and I’m so grateful to everyone who’s joined the paid version A Gardening Year,—your support truly means so much!

If you’re new here, I write letters centered around the work of building my regenerative flower farm, Tiny Meadow, sharing insights and reflections plus gardening tips along the way. I also give myself room to wander into other topics when they call to me, like this one. As a flower farmer, florist, naturalist, and deeply curious person my writing is always grounded in the rhythms of the natural world, even when it meanders.

I also can’t wait to send out my first handwritten letters to new founding members this Spring Equinox (here’s a sneak peek of what it will look like!):

Each month, I’ll share seasonal reflections like this. For those wanting more, A Gardening Year offers hands-on tips and seasonal ideas.

Next up, mid-January for members: setting up an indoor seed-starting system to get a heads up on spring planting. Until then, I hope this season brings you moments of rest, calm, and curiosity.

Thank you for being here!

Love,

Rowen

For the Lonely Gardener:

You and I are Earth, 1661, creator unknown, Found in a London sewer. Tin-glazed earthenware plate.

The full version of Wild Geese, Mary Oliver

Emily Dickinson’s Envelope Poems

Rereading Braiding Sweetgrass

From the edge to the center- Lisa Olivera

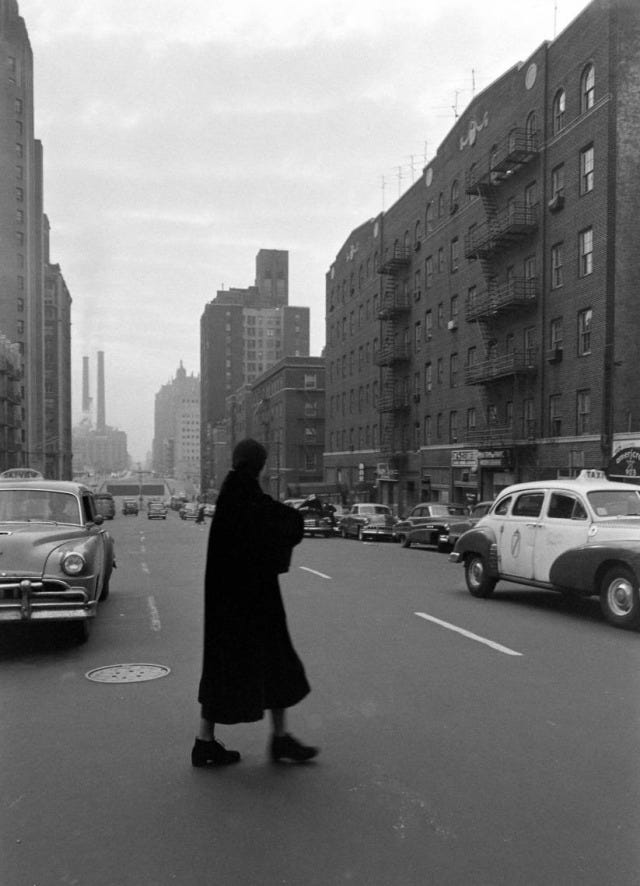

The story of Greta Garbo - “I want to be alone”, the piece Chasing Solitude, and a photo of her, post-retirement, walking the streets of New York City:

I used to grow Christmas cacti in the winter, enjoying the luscious red blooms during the winter. I love the idea of bulbs. What a lovely post!

This is so beautiful Rowen~thank you for sharing. I too plan to re-read Braiding Sweetgrass this springtime along with the gentle planting of an abundant garden. While anticipating is helping release some of the dull ache from the winter lonelies, I was wondering when things would shift and recently felt something positive stirring. Spring is coming, thank goodness.