On starting a nature journal

Returning to practice, prompts for fall nature journaling

Dear Reader,

It’s mid-October, and the fog is so thick that the sun is made crystalline, a white circle behind a wall of grey.

I sit at my writing desk this morning surrounded by marigolds arranged in various bud vases, creamy yellow-orange ruffles tipped in black, their centers deepening as they mature.

As a florist, arranging flowers is a practice I continually return to by obligation, though many times the practice comes from a deeper need to create. This time, there was a certain alchemy in the slightly battered marigolds that compelled me to action. I sit surrounded by them, their smoky, spicy scent of camphor mingling with the crisp fall air.

I’ve been thinking about all the practices I hold and continually return to, especially after a particularly difficult growing season on the farm, and what it means to keep momentum in each of my roles.

Where does the alchemy come from? What does it all lead to? How do all the different, seemingly amorphous shapes and compilations fit together?

The garden is at the center. It informs and grounds all of my other practices. I write about the farm and about being a gardener. The farm grows the flowers I arrange as a florist, an offering to my community that supports me financially. The farm also continually informs my work as an aspiring naturalist as I learn how to walk the line between growing to sustain my work and growing to support local ecologies. Part of that work is getting to know the land and ecosystem that contain the farm, which in turn informs my work in the garden. The cycle continues.

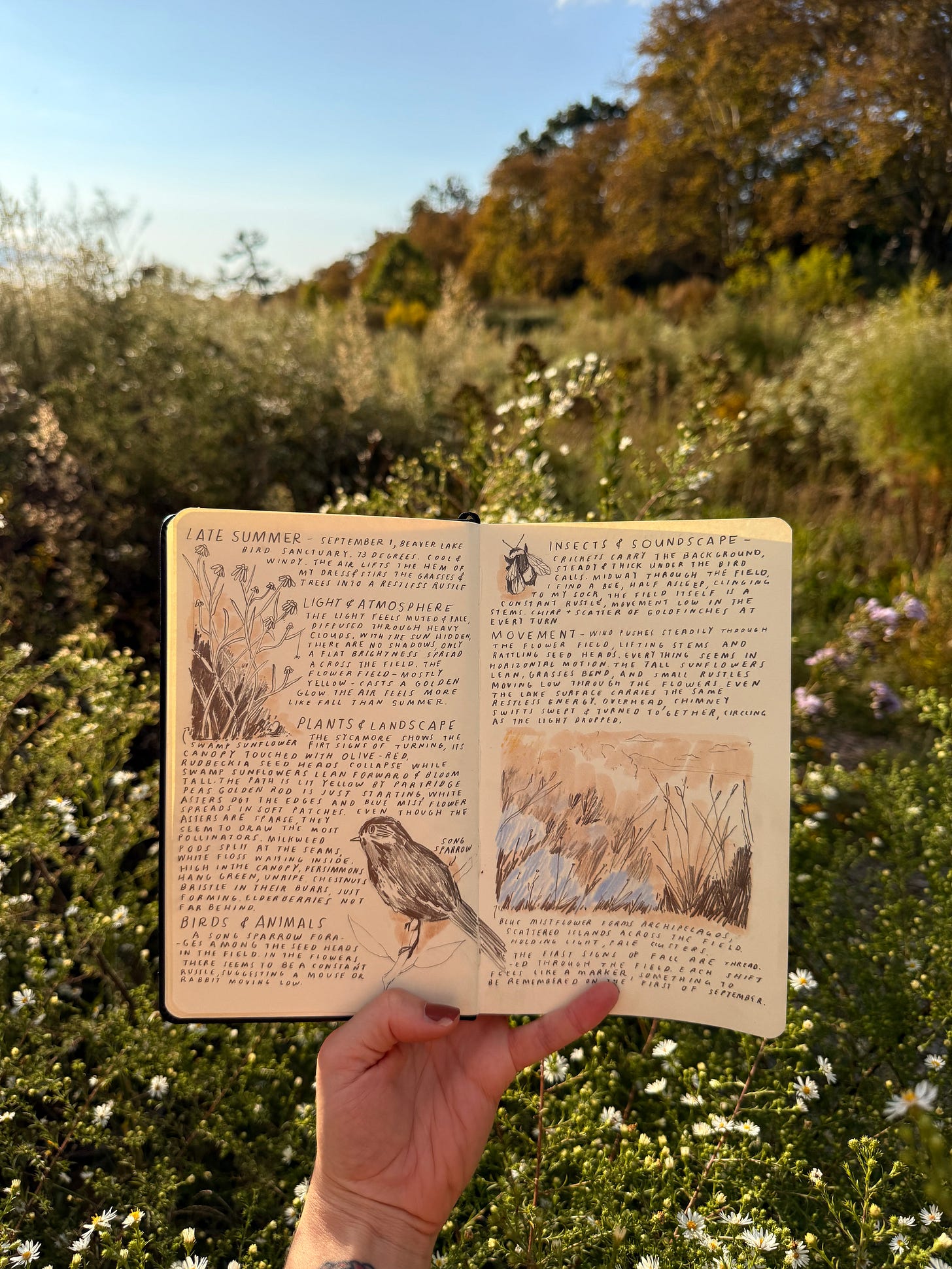

One of the practices that supports this is my nature journal, which I’ve returned to on and off over the years. This year, I’ve dedicated myself to it more regularly, and it has deepened and enriched all my other creative practices.

Why keep a Nature Journal

To keep a nature journal is to practice bioregional literacy: to pay sustained, local attention to the living world around you, its patterns, rhythms, and language. Through this practice, the world ceases to be a blurry backdrop and becomes relationship. The key to developing bioregional literacy is not just paying attention, it’s sustained attention over a period of time.

Sustained attention to the natural world resists our cultural impulse to move on once we’ve “named” a thing. The work of my nature journal is to stay with what I’ve seen, to circle it again and again until its context begins to unfold.

Bioregionalism begins with the premise that where you are shapes who you are, that geography, watershed, and season are not scenery but kin.

A nature journal maps that kinship. It situates you within your location’s specific language, its smells, weather patterns, migrations, and native plants. It trains you to know your region as a body and, in doing so, to take responsibility for it.

A nature journal especially keeps that thread alive in an age of digital detachment. It’s a way to refuse the virtual in favor of the real. Noting the weather may seem simple, but paying attention to the weather, the temperature, the season in a physical journal is one of the simplest things we can do to tether ourselves to physical reality.

in David Abram’s Becoming Animal:

“If we speak of things as inert or inanimate objects, we deny their ability to actively engage and interact with us—we foreclose their capacity to reciprocate our attentions, to draw us into silent dialogue, to inform and instruct us.”

Your nature journal becomes the place where that dialogue happens. The act of writing or drawing is not just recording but listening. The more you attend, the more the world seems to speak back through shifts in light, through the return of a certain bird. When you return to the same place over a sustained period of time, you start to notice how each return is completely new.

A cloud is not a noun but a verb. So is a forest, a field, a body. A nature journaling practice over time makes this visible.

Initial struggles

One of the things I continually struggled with was the pressure of creating perfectly beautiful pages that were accurate to the genus or species of the plant. While I found this work deeply compelling and absolutely worthwhile, I simply could not commit to the amount of time and effort each entry would ask of me for this level of attention, along with all the other work I was doing.

Once I started to lean less on realism and more into my impression or feeling of the plant—just getting it down—the pressure eased, and I was able to have more fun. I leaned into my own style, and the practice began to feel more natural while also taking up less time.

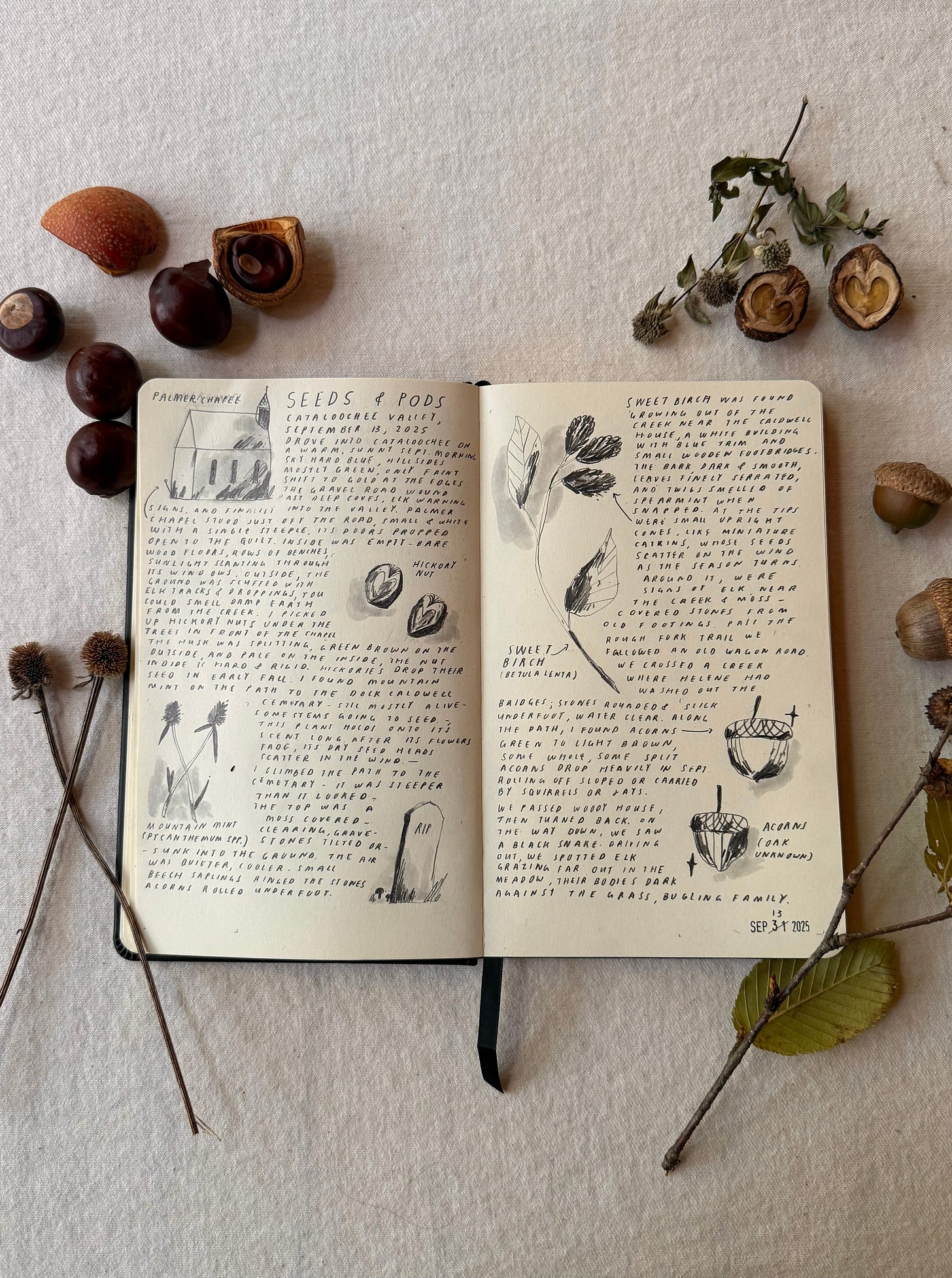

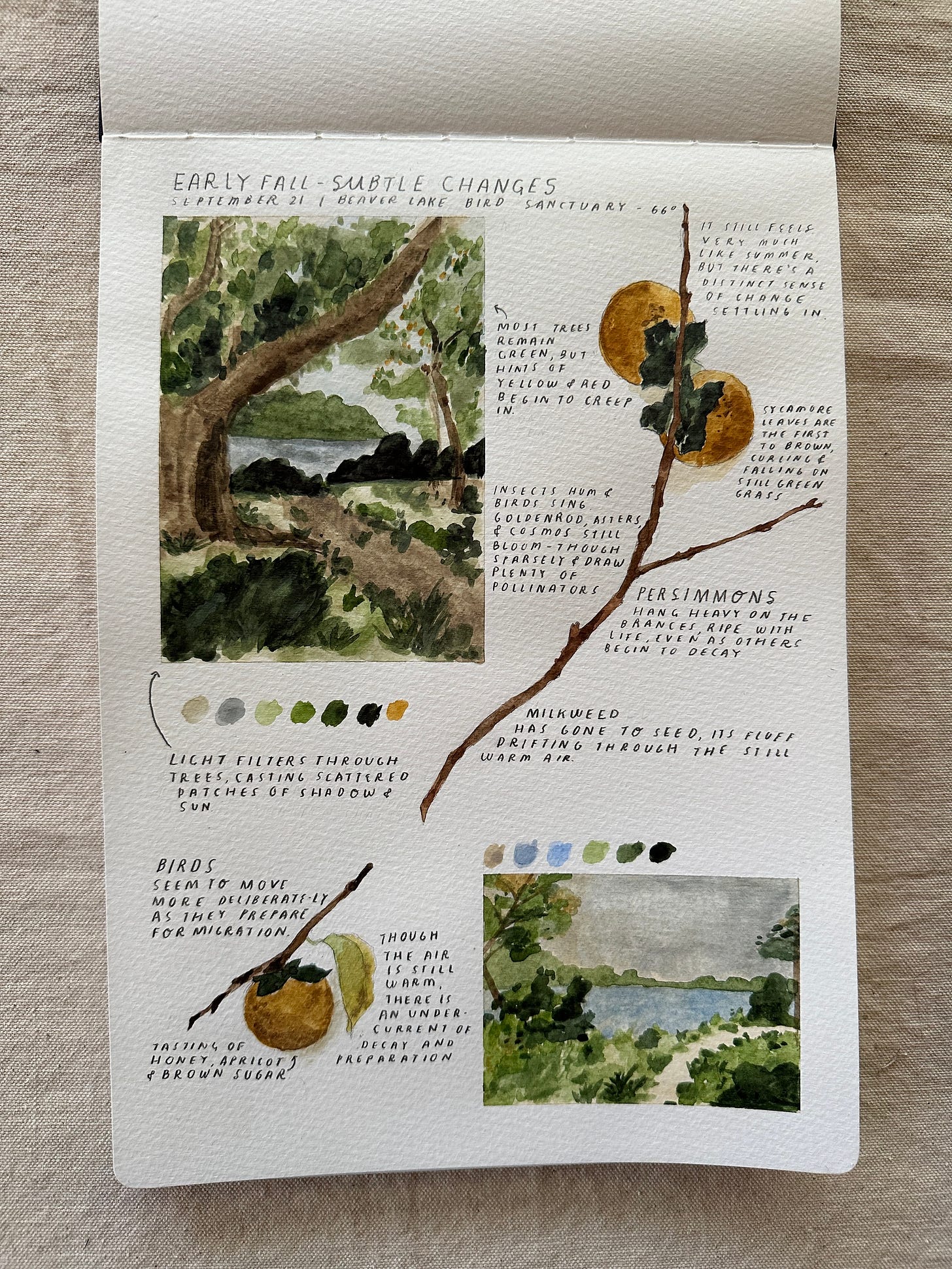

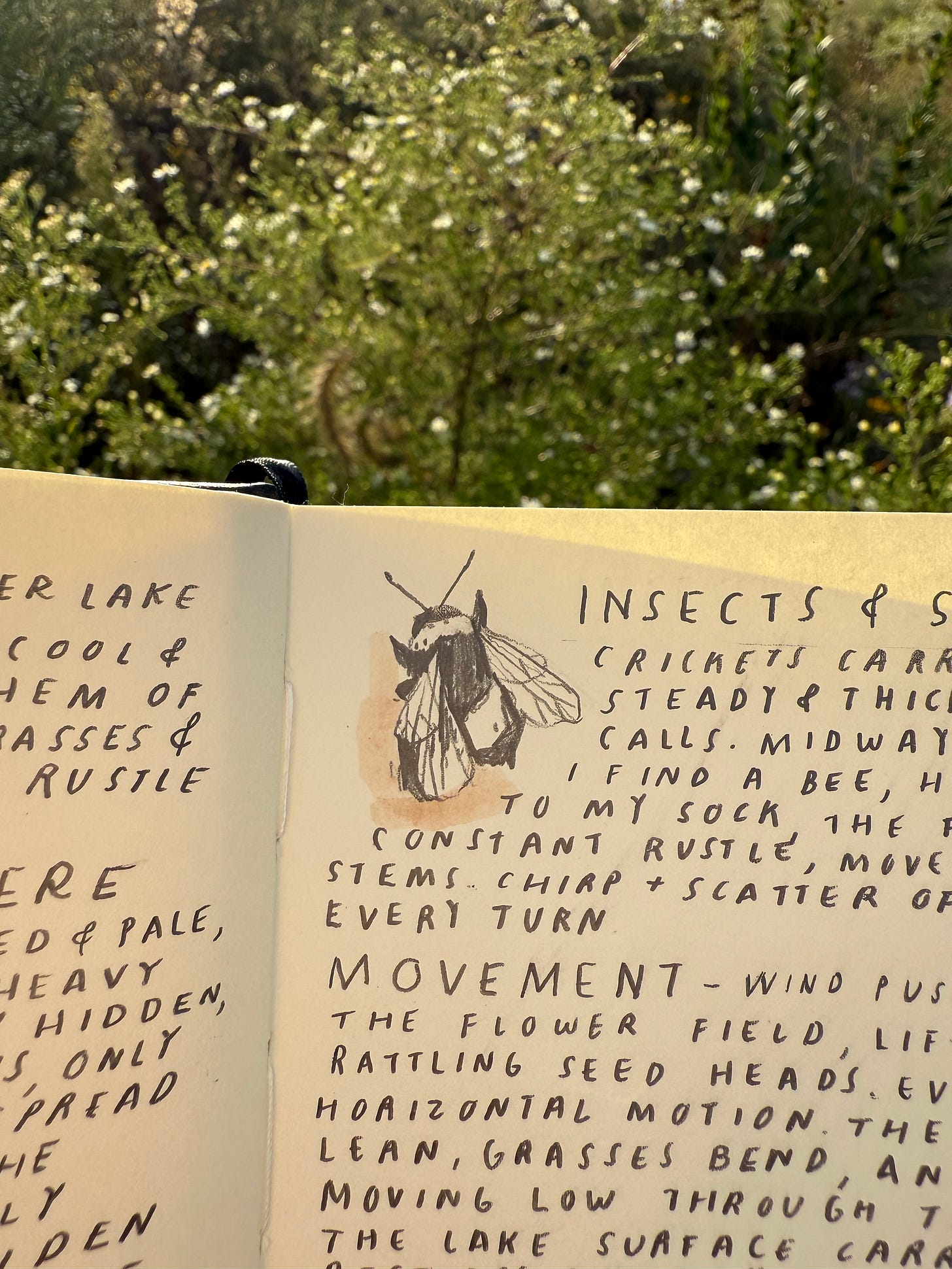

Another challenge was the pressure of a blank page, especially out in the field. I needed some kind of structure or purpose to guide me, otherwise I’d find myself unsure of where to begin or end. I started following seasonal prompts and themes, seeds and pods in September, a fall wildflowers entry, a focus on pollinators, and so on. This gave me something specific to focus on, seasonal guardrails that made the practice feel freer. I’ve included the fall prompts I’ve been following below.

Mediums

Watercolors and nature journaling go together perfectly. I love using watercolors in this practice, and there is a reason why so many botanical illustrators and landscape painters use them when drawing nature. It’s a relatively forgiving medium you can take with you on the go, and it creates a buildable palette that captures the feeling and colors of the natural world.

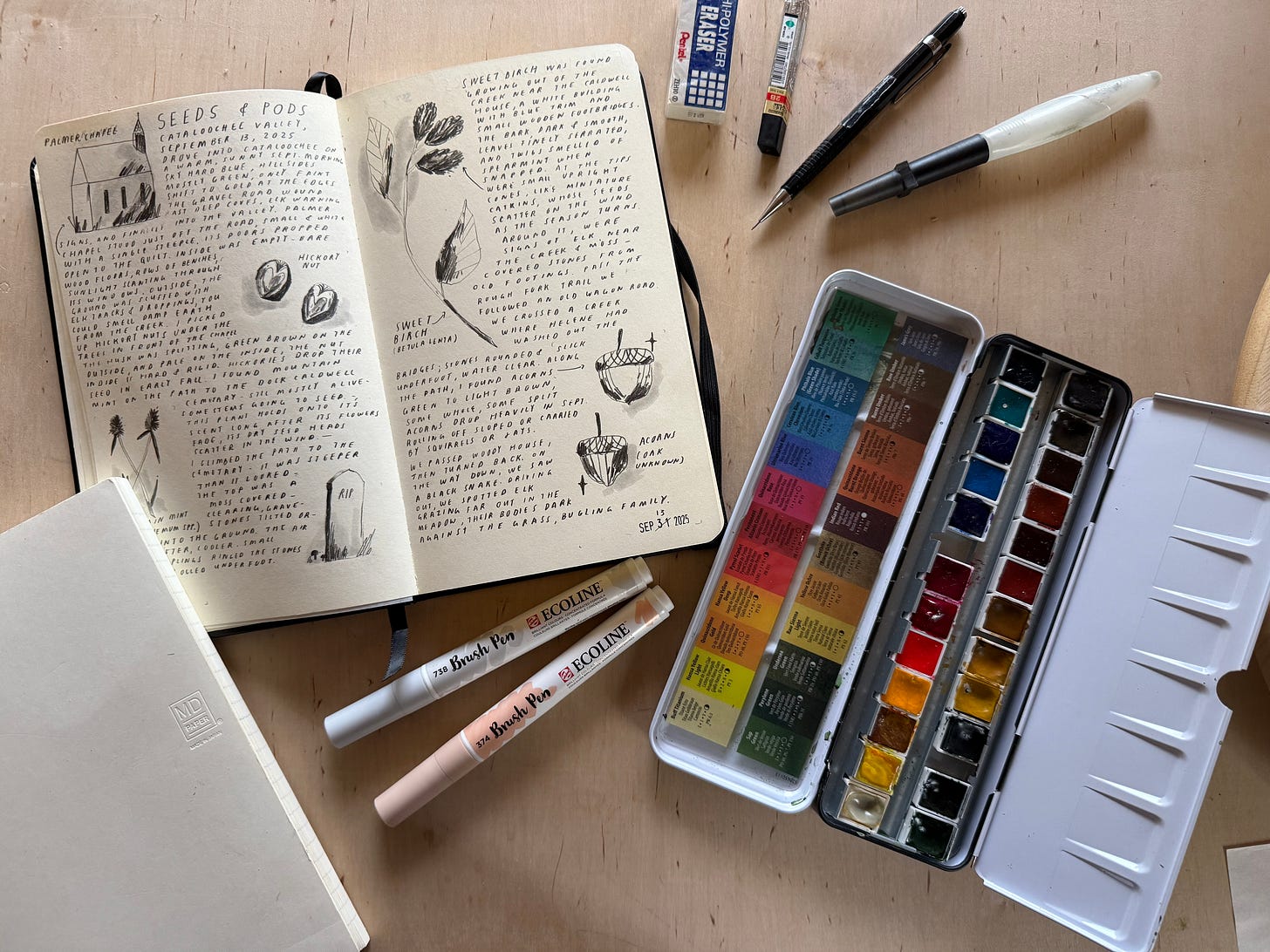

I’ve gone through a lot of medium testing and loved using watercolors, but in order to lessen as many barriers to this practice as possible, I chose to simplify my materials, using only two tools most of the time: the humble mechanical pencil and a carefully chosen notebook that is multi-media in case I want to use different materials or have time to expand into more detail.

Favorite Materials

Notebooks

Midori A5 Grid: My go-to when using pen or pencil only (also what I use for morning pages).

Talens Art Creations Sketchbook: Creamy white, absorbent paper that holds up well to watercolor here and there, good for mixed media.

Pencils

Pentel Sharp Mechanical Pencil with 2B Lead: This softer lead creates darker marks. I use it for both writing and drawing. It’s much darker than a standard pencil, which allows for greater variation in shading. It also pairs well with the above Talens Sketchbook, with minimal smudging.

Watercolor Brush Pens

Ecoline Brush Pens: Good for adding a pop of color or a shadow behind illustrations:

Watercolors

Daniel Smith Watercolors: On the pricier side, but the shades, especially the greens and nature tones, are unmatched. I also use a Derwent water brush.

The Process

1. Choose a seasonal prompt

I start by mapping out the prompts I want to follow depending on the season. Once I have the prompt, such as “seeds and pods in September,” I choose a location that fits: mushrooms in the deep forest, a wildflower field in higher elevations, or a dry meadow full of late-summer seed heads.

2. Research and plan

Beforehand, I do a bit of research on the area so I know what to look for. I usually map out the hike and jot down questions or guided prompts in the notes app on my phone. This helps me avoid overwhelm and keeps me attuned to what the season is offering. I also make sure to have a nearby place I can return to often, like the bird sanctuary near my house. Having an easy-to-access location reduces barriers to consistency and helps me maintain momentum when I do not have time to travel far.

3. Observe in the field

When I am out there, I do not try to create a finished journal entry. I use my Midori or notes app to record what I notice: plants, birds, weather shifts, the smell of wet leaf litter, or any small details that resonate. My goal is to stay present and observe. Working from quick notes later allows the experience to settle before I translate it onto the page.

4. Create the entry afterward

Once I am home, I try to create the entry within 48 hours while the moment is still fresh. I start by sketching a loose layout in my Midori, then expand my notes into a written entry into my sketchbook, leaving blank spaces for illustrations or tables. I fill in drawings as I go to avoid smudging the text.

5. Add personal details

I include whatever feels connected to the purpose of the entry, such as plants and weather, but also small personal details like meeting a friend on the trail or a thought that surfaced while walking. These fragments keep the entries rooted in real life, not just the landscape. They remind me that the journal is as much about relationship as it is about record.

Prompts for your Fall Nature Journal